Nobody is Exempt

Isla’s first few months at the new ABA clinic were going great. She was learning a ton, and she really enjoyed seeing new therapists and kiddos each day as the clinic grew.

However, with each new therapist came a new opportunity to test the limits and boundaries of her behavior.

In about the second or third monthly parent training, I learned of a new behavior that was the most disturbing for me as a mother, a woman, and a healthcare professional.

We were reviewing the graphs of Isla’s different behaviors, and the BCBA was showing me how they would spike when a new therapist came on board and then dissipate over time.

As she flipped through the charts I saw all of the behaviors I was already familiar with: Aggression, flopping, elopement, urinating off the toilet…some were getting better (elopement had clearly decreased), while some, like urinating off the toilet, clearly spiked with each new therapist.

Flopping blew my mind because she only did it at school, but it was nothing new.

But then we flipped to a chart labeled “Disrobing,” and I stopped in my tracks.

“Whoa, whoa, hold on. What do you mean ‘disrobing’?”

Eileen explained to me that sometimes when urinating didn’t work, Isla would take off her clothes because she knew the therapist would have to look away and stop the activity until she put them back on.

My stomach went sour and I wanted to cry—and vomit—but I tried so hard to stay composed, because I needed to know the details.

“So do you mean all her clothes?” I asked.

“Yes,” Eileen confirmed.

“No, hold on I mean do you mean she is completely naked?”

“Yes,” she said again.

I was horrified. My mind started racing, and I pictured Isla standing in a room with therapists—men and women—completely naked. Wow.

Keep in mind that this ABA clinic had continuously recording cameras in every therapy room and in every hallway so parents could request to see anything and everything we wanted.

I knew that from day one, so I never really worried about her being one on one with a therapist.

I knew that was the setup she needed to learn and to avoid other distractions. But disrobing? I was paralyzed in my chair.

My first thought was, I don’t care what the ABA rulebook says—if my kid is taking off her clothes, you damn well better put them back on quick!

Call a female into the room and put her shirt back on before it escalates.

But that was not the ABA model, and I knew that. I felt sick to my stomach and absolutely embarrassed. Ashamed.

I didn’t know that was happening. Was I supposed to allow that?

Eileen caught on to my “I-am-about-to-throw-up” face quickly and paused.

With my eyes lowered, I quietly asked, “Are there shades on all the windows?”

Eileen said they had to get shades because of disrobing issues—not just with Isla but with other kids, too.

“So this is a typical behavior of autism?” I asked.

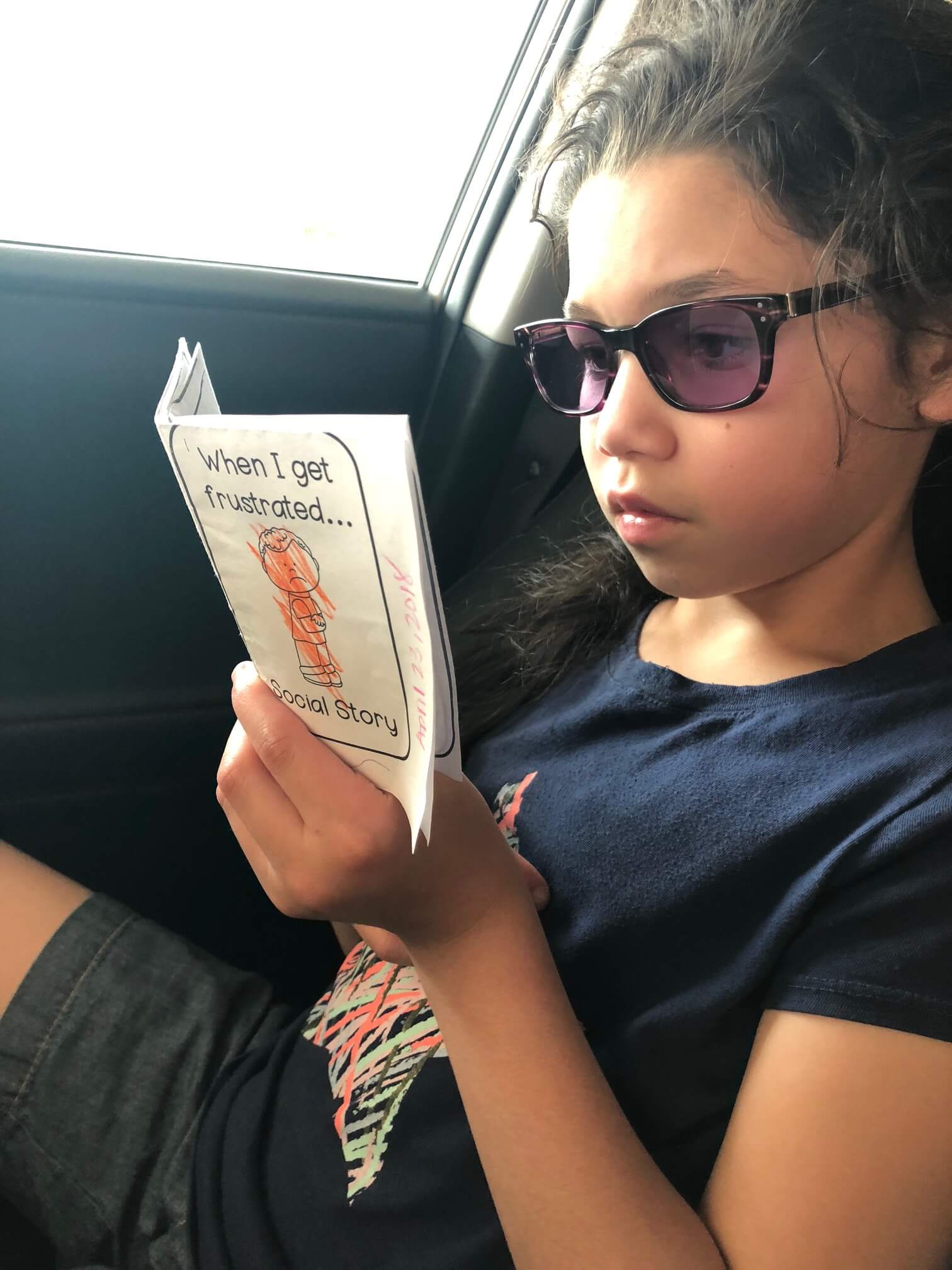

She said that while not all children do it, disrobing is not uncommon, and it typically happens as a response to frustration or sensory issues.

As was with each behavior, the disrobing escalated to an almost daily occurrence before it dissipated, but boy did it escalate.

I was at work one day when I got a phone call from the ABA clinic.

Apparently, Isla was experiencing an extended episode and had remained disrobed for a lengthy amount of time.

They were calling me because the therapist in the room had turned her back to allow Isla to get dressed, but when the therapist turned back around, Isla was not dressed, and the play dough that had been on the floor in front of her was no longer there. Where was the play dough?

I did that crazy speed walk to my car. You know, the one where you don’t bend your knees and you want to make it seem you are not in a hurry, but you totally look like a fool in a hurry?

As I was driving to the clinic, I called my husband, Greg, in hysterics.

You have to understand that Isla did not act like this at home—ever. So when she did this during therapy my first reaction was anger. I was so mad at her.

Greg, of course, was calm.

He told me to check her to make sure she had not eaten the play dough and reminded me not to let the therapists or Isla see how upset I was.

Yeah buddy, easier said than done, I thought as I hung up the phone.

When I walked into the clinic, the therapist met me at the door, clasping her hands. “I am so sorry,” she said. “I just want you to check her to make sure—well, because we don’t know what she did with the play dough, and we can watch the video back, but it will take time to load it and, well…”

All I could mutter was, “Where is she?” I was led to a room, and I asked to go in alone.

When I opened the door, my beautiful, tall seven-year-old girl, who was now fully clothed, stared back at me with big hazel eyes, nibbling on her finger nails. She was terrified.

She looked so worried, scared, lost.

It was a look I had gotten used to seeing, but this time it was intense.

All of a sudden all of my anger towards her—my rage towards autism, my embarrassment of her behavior—melted away as I knelt down and held her.

We hugged each other tight and cried together.

As I cried I quietly whispered, “God please help my little girl. Please don’t let her suffer this anymore. Please help us, Jesus, to cope with this. Give Isla peace, please.”

Then I just kept saying in her ear, “It is OK. It is OK. Everything is OK.”

It was one of the first times that Isla felt that something was wrong with her and that she couldn’t control it. She didn’t fight it.

She let herself cry and let me hold her and rock her.

After a few minutes, I pulled her away, looked right in her eyes, and said, “Isla I need you to tell me what you did with the play dough.”

She whispered back, “I not know.”

So, we wiped our faces and walked to the bathroom together, where I undressed her and checked her head to toe. No play dough to be found.

I walked out that day feeling totally defeated.

I had no appetite that night, and I struggled as I tried to tell my husband all that had happened.

I realized that day that nobody is exempt from the ugly, scary side of autism. Nobody.

Written by, Dr. Lisa Peña

Dr. Lisa Peña is a Today Show Parenting Team contributor and the founder of The M.o.C.h.A.(TM) Tribe which stands for (M)oms (o)f (C)hildren that (h)ave (A)utism. She is the author behind The M.o.C.h.A. Tribe Diaries which is a website/blog devoted to squashing the idea that autism has a single story and author of a newly published book, “Waiting for the Light Bulb” available on Amazon. She is a rookie author but a professional mother of a child with an incredibly unique subset of autism called, pathological demand avoidance (PDA). Dr. Peña is a proud coach’s wife, a clinical pharmacist, passionate public speaker and a busy mom of three who happily resides in South Padre Island, TX. For more information, visit www.mochatribediaries.com.

Interested in writing for Finding Cooper’s Voice? LEARN MORE

Finding Cooper’s Voice is a safe, humorous, caring and honest place where you can celebrate the unique challenges of parenting a special needs child. Because you’re never alone in the struggles you face. And once you find your people, your allies, your village….all the challenges and struggles will seem just a little bit easier. Welcome to our journey. You can also follow us on Facebook and subscribe to our newsletter.